The Old Navy

Like Swatting Bees in a Telephone Booth

By Commander Ted Hechler, Jr., U. S. Navy (Retired)

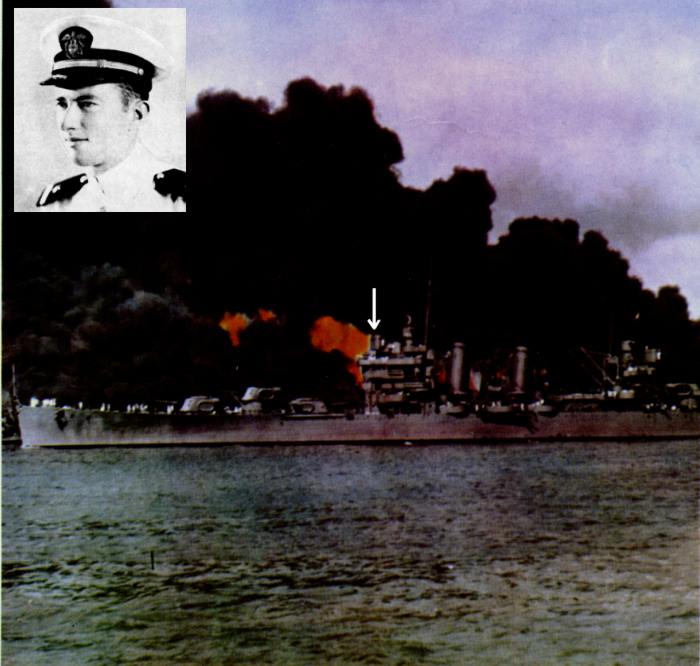

When this photograph was taken by the Japanese, it looked as though all the U. S. ships, including the author’s

Phoenix, arrow, would pay dearly for the front row seats they occupied in the unfolding drama

The customary prewar ways lasted right up to the time war started. I remember 6 December, the day before the Japanese attacked. Saturday morning inspections were an institution in the Navy before the war. On that particular day, the inspector was Rear Admiral H. Fairfax Leary, Commander Cruiser Division Nine and Commander Cruisers Battle Force. Leary had been in the Job since early In 1941 when he relieved Admiral Husband Kimmel. I was then an ensign, serving in the new light cruiser Phoenix (CL–46). The men were in their whites, lined up in rows for personnel inspection. When it came to the inspection of the ship herself, Leary had on his white gloves so he could check for dust. How irrelevant it would all seem 24 hours later.

The end of Saturday inspection was the traditional signal for liberty call, and I went ashore for the day and evening with two fellow ensigns, Garth Gilmore and Ellsworth Marcoe. We returned to the ship probably about 0200 on Sunday morning, planning to sleep late. We were to be in leave status all day Sunday and planned to return ashore again on Sunday afternoon. In the meantime, the Phoenix would provide a free night’s lodging, which was a consideration for some of us less affluent ensigns.

I was awakened at 0755 by the loudspeaker, which was saying, “Set Condition III in the antiaircraft battery.” This was an alert condition in which only the duty section was involved, and I was not planning to respond. Instead, I grumbled something to my roommate, who was the same Ensign Gilmore of the night before. I complained about yet another damned drill, and in Pearl Harbor on a Sunday morning, no less. In probably no more than 10-20 seconds this was all changed. I heard the sound of feet running on the deck overhead. Then came the sounds of the Klaxon horn and an announcement, “All hands, general quarters.” This meant us, and we started to move out of our bunks. The voice on the loudspeaker now became shrill as the message changed to “All hands, general quarters! Man the antiaircraft battery. This is not a drill!” The words “This is not a drill” were repeated over and over, almost pleadingly.

If I needed anything further to accelerate me, it was the sound of our .50–caliber machine guns opening fire overhead. I quickly drew on my clothes and raced up the ladder to the main deck. I shall always remember the sight of our communication officer, Lieutenant William K. Parsons, attired in immaculate whites, standing there waving his arms at us. He held a batch of papers in his hand (he had evidently been on duty) and was shouting, “Come on, come on. It’s war, it’s war.” By now, I was flying up three more decks to my station in sky forward, which controlled the four 5–inch/25 antiaircraft guns of the starboard battery. I was propelled on my journey by the sight of a torpedo plane that flew past the Phoenix at deck level. It carried a big red ball on the side. As I reached my station, our battery was already training out. The awnings which were still up from the admiral’s inspection had to be taken down so the guns could train out. Locks were chopped off the ammunition boxes.

The Phoenix was moored that morning between two buoys in a berth known as C–6, located near the Aiea landing, She was about 1,000 or so yards from the north end of Battleship Row along the east side of’ Ford Island. The Nevada (BB–36) was the nearest of the battleships to us. Also near the Phoenix was the hospital ship Solace (AH–5). Because of the lack of high–level horizontal bombers — the kind of planes I was capable of directing fire at — during the initial phases of the attack, I found myself an unwilling occupant of a front–row seat from which to witness the proceedings. The sight that my eyes beheld from that perch at the forward part of the superstructure is difficult to believe, even today. The sky seemed filled with (living planes and the black bursts of exploding antiaircraft shells. Our batteries were among those firing shells in “local control,” which meant that the fire was originated from the guns themselves. The Japanese planes were too close to take advantage of the more sophisticated automatic control, which was normally provided by my station. In essence, the guns were laying out a pattern of steel in the hope that the Japanese planes would fly through it and be damaged in the process. I have often described the experience as akin to trying to swat an angry swarm of bees in the confines of a telephone booth. To make matters worse, our shells were set with a minimum peacetime fuze setting which would not permit them to explode until they had reached a safe distance from the ship. In addition, some of the fuzes were defective, with the result that the unexploded projectiles were coming down ashore. Our best weapons Under those conditions were the machine guns, which accounted for a number of enemy aircraft.

By shortly after 0800, the harbor was a riot of explosions and gunfire. I looked at the battle line, from which huge plumes of black smoke were rising. As I watched, I saw the Arizona (BB–39) wracked by a tremendous explosion. Her foremast came crashing down into the inferno. Since I was in the corresponding station in my own ship, I naturally thought about what my own fate might be in the next few minutes. Bombs were exploding on the naval air station at Ford Island and the Army air base at Hickam Field. A Japanese torpedo plane came down our port side. It couldn’t have been more than 150 feet above the water and looked as if the pilot had throttled down, having just Launched his torpedo at the battle line. He banked to the left as he got opposite us, as if to turn away. I could see .50–caliber tracer slugs going right out to the plane and passing through the fuselage at the wing joint. Suddenly, flames shot out from underneath and he continued his turn and bank to the left until he had rolled over onto his back. A great cheer went up from our crew, because his demise was apparent. Unfortunately, he crashed onto the deck of the seaplane tender Curtiss (AV–4), inflicting a number of casualties among her crew.

On our starboard side, the old repair ship Vestal (AR–4) was beached, with her port side blackened by fire. Another plane came in, low over the water to our starboard quarter. This time, I saw a cross fire of tracers from the Phoenix and other ships. There was an explosion on the plane, and in the next instant there was nothing left but its debris descending to the water. Moments later, I heard the "zing" of a bullet whistling by. Later, we discovered a hole in the shield of the Range Finder 5 (flagplot) below us. Of course, the air was so full of flying bullets and shrapnel by that time that it was impossible to tell the source, but that bullet constituted the total damage inflicted on the Phoenix that day.

The first wave of the attack seemed to end sometime around 0825 or so. About that time, the Phoenix attempted to get under way. We cast off and tried to go out around Ford Island, via the north channel. Signals from the naval base informed us that enemy submarines had been spotted and that the submarine nets at the entrance to the harbor were closed, or being closed. So we were directed to return to our mooring. At about 0840, the second wave hit us. Motor boats were making hurried runs across the harbor to return those officers and crewmen who had been ashore for the weekend. I can still see them making their way to our ship amidst the splashes of bullets and falling shrapnel. During this period our captain and executive officer returned aboard.

The Second attack featured some high–level bombers which brought my director into action. We fired numerous rounds at the aircraft, but much to my dismay, I did not see any flak bursts from our shells. We later replaced the ammunition, but I never learned the cause for the failures. The second attack inflicted further damage on Pearl Harbor, but for some reason, the Phoenix did not come under attack. Perhaps it was because our ship’s slim outline didn’t present as attractive a target as other ships and because we were moored alone and thus harder to hit.

The swarms of angry Japanese bees had gone as Ted Hechler (arrow and inset) viewed his ship’s departure for

the open sea from his perch in sky forward.

At any rate, shortly after 1030, when the second attack was over, the Phoenix did cast off and began her sortie. While our guns were still firing, we attempted to steam out the north channel. Once again, warning of submarines in the channel forced us to turn around and head back toward our berth. Then we went out the south channel. As we proceeded past the once–proud battleship row, we turned our binoculars on the terrible scene. We saw ship after ship in devastated condition, and the hangar on Ford Island was nothing but a skeleton of charred girders. Scores of ruined patrol planes lay in a heap on the runway. Flames were still licking up from Hickam Field. After another submarine warning and one last look back to the shipyard where the Pennsylvania (BB–38) lay In dry dock, apparently undamaged, we streaked for the open sea at 30 knots.

As we headed out, we could hear the cheers from the sailors on the shore. One airman, astride the pontoon of his overturned floatplane, waved his clenched fist in the air as we passed through the harbor entrance. We finally made the open sea unscathed. Although we affectionately referred to our ship as the “Phoo Bird,” she rightly deserved the nickname “Lucky Phoenix” — both that day and later in the war. Her name, although deriving from the city in Arizona, also comes from the bird in an ancient fable. When consumed by fire it rose from it’s own ashes. Rather apt, in retrospect.